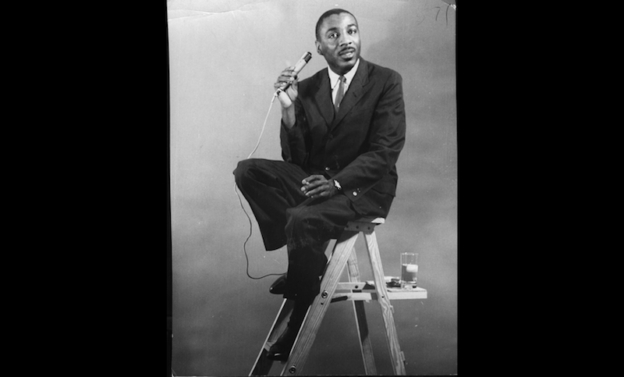

The writer and date having photo taken with Dick Gregory for $10. Gregory’s nephew, comedian Mark Gregory, is at top right.

Dick Gregory died Aug. 19, 2017, in Washington, D.C.

Before Richard Pryor, before Eddie Murphy, and before Chris Rock, Whoopi Goldberg and Dave Chappelle, there was Dick Gregory, who in the 1950s and ’60s smashed through the color barrier separating black comedians from white audiences. Once dubbed the black Mort Sahl for his political humor, he is one of the lesser-known pioneer black comedians — or, as he would say, comedians who happened to be black — in large part because he put activism ahead of show business.

On March 26, 2017, the 84-year-old comic, civil rights activist, author and holistic health advocate performed for one of the last times before his death, at a nearly full house at the Improv in West Palm Beach. It was kind of like going to see Bob Dylan, or back in the day, Lenny Bruce. You go to pay your respects, hope they do their best, but prepare for something less, which is what happened at the Improv.

Not that the audience was disappointed. We got to see vintage Gregory. Feisty, contrary, racial, cosmological and conspiratorial. Lots of MFs, b- and n-words. (His nephew, rising comedian Mark Gregory, who served as Gregory’s warmup act, chose to go with the anachronistic “Negro” instead.)

Black, or what in the 1950s were called Negro comedians, took two new paths to break into the mainstream — the old path was self-denigration, as epitomized by Stepin Fetchit. Some of Gregory’s peers, like Bill Cosby, avoided controversial subjects and kept things folksy, similar to Will Rogers, Bob Hope or Jerry Seinfeld. Others, like Godfrey Cambridge and Gregory, took the riskier route of social satire, tapping into a strain of American humor that runs through Mark Twain, Lenny Bruce and George Carlin. Actually, it’s more a matter of degree. To some extent, all comedians combine what might be called silly and serious humor. Like most people, entertainers try to find a combination of representing and assimilating that works for them, professionally and personally.

Richard Claxton Gregory was born into poverty on Oct. 12, 1932, in St. Louis, Missouri. He became a track standout at Sumner High School, and in 1951 he got an athletic scholarship to attend Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, before and after being drafted into the Korean War. (This writer was born and went to college in Carbondale, and local lore has it that Gregory was the first black person to integrate the town’s Varsity Theater, by refusing to sit in the balcony.)

ABC Close Up Report – Walk in My Shoes (1961). Nicholas Webster’s documentary explores the state of urban black America, featuring what may be Dick Gregory’s first TV appearance. His segment begins at (15:16), but there’s also footage of Malcolm X, CORE founder James Farmer, and regular people discussing race and sex, among other issues.

Gregory left school before graduating and moved to Chicago, where he worked at $5-a-night comedy gigs and met his wife, Lil. They had 11 children, including one who died shortly after birth. Because of his busy schedule, he admits to having been an absent father. His stock line is, “Jack the Ripper had a father. Hitler had a father. Don’t talk to me about family.”

He got his big break in 1961, when Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner took a liking to his sardonic takes on race and current events, and hired him for an extended stay at the Playboy Club. Gregory’s disarming sense of humor enabled whites to laugh, sometimes at themselves, while being confronted with inconvenient truths. An example of one of his early jokes is on his website: “Segregation is not all bad. Have you ever heard of a collision where the people in the back of the bus got hurt?”

From the Playboy Club, he began playing better venues, like San Francisco’s hungry i, and got on Jack Parr and other TV shows. In 1963, his first autobiography, “Nigger,” was published and became a best seller. (In the book, he says he chose the title so that whenever his mother heard the word in the future, she’d “know they are advertising my book.”)

But then he pulled a Dave Chappelle and withdrew from the spotlight. Inspired by leaders like the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., he joined the Civil Rights Movement and used his celebrity status to address such issues as segregation and voter registration. While contemporaries like Cosby, Cambridge and Nipsy Russell were getting their shots at stardom, Gregory was protesting world hunger and other issues. He went on dozens of fasts, sometimes lasting more than 40 days, and for two-and-a-half years he ate no solid food to protest the Vietnam War.

He ran against Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley in 1966, and as a write-in candidate for president in 1968. According to his website, “After the assassinations of King, President John F. Kennedy, and Robert Kennedy, Gregory became increasingly convinced of the existence of political conspiracies.” With JFK conspiracy theorist Mark Lane, in 1971 Gregory co-wrote “Code Name Zorro: The Murder of Martin Luther King Jr.”

In 1973, Gregory moved his family to Plymouth, Massachusetts, where the once overweight smoker became a nutritional consultant. He says he first became a vegetarian after seeing his pregnant wife kicked by a cop, and not having the courage to fight back. He vowed that he would never “participate in the destruction of any animal that never harmed me.” In the 1980s, he founded a company that sold weight-loss products, and he drew media attention when he started a fat farm in Ft. Walton, Fla., for the morbidly obese.

In 1996, he returned to stand-up with a well-received one-man show, “Dick Gregory Live!” Also in 1996, he picketed CIA Headquarters to protest allegations that the agency had started the crack epidemic by smuggling cocaine into South-Central Los Angeles. He was arrested, as he has been many times over the years.

In 2000, Gregory was diagnosed with lymphoma, a deadly form of cancer. That same year, a three-and-a-half-hour tribute was held in his honor at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., hosted by Bill Cosby, with appearances by Coretta Scott King, Stevie Wonder, Isaac Hayes, Cicely Tyson, and Marion Barry, among others. Refusing chemotherapy, he used alternative medicine to beat the disease, and became a lecturer on diet and ethics.

Wikipedia lists 16 albums and 16 books on his resume, but according to the IMDB website, he has never been in a major motion picture, although he has appeared as himself in several documentaries. His film credits include Rev. Slocum in “Panther” (1995), a bathroom attendant in “The Hot Chick” (2002), and a blind panhandler in the TV show “Reno 911” (2004). Nevertheless, in 2015 he received a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, for Live Theatre/Performance.

To the end, he maintained a grueling schedule of up to 150 shows, lectures and interviews a year, many of which are on YouTube, and he had an active Twitter account. Before coming to West Palm Beach, he was at the Improv in Houston, and from Florida he headed to New York City, for two shows at Caroline’s on Broadway.

At the Improv at West Palm Beach, Gregory was, in a word, grouchy. When introduced to the mainly older and black audience, the comedy icon didn’t appear for several minutes, apparently because he was in the restroom. Once he doddered on stage and slumped into a chair, he began muttering. When a woman sitting about 10 rows back shouted that she couldn’t hear him, he snapped back, “you shoulda sat closer,” which got a laugh.

He acknowledged his age but bristled at the term “elderly.” “I’m just old,” he said.

He talked about race, religion, sex and politics, including Obama and Trump. He said he was disappointed that Obama hadn’t gotten more done when he was in the White House, but that comparing him to Trump forever destroys the myth of white superiority.

He made many other wry observations, but like Lenny Bruce, he was less funny the more he indulged his obsession — for Bruce, it was his legal woes, in Gregory’s case, the many conspiracy and dietary theories he has accumulated over the years. He still thinks “agents” are out to get him, and that Oswald didn’t kill JFK.

He had brought along numerous visual aids, including newspaper clippings, magazine covers and photos of himself with MLK and Muhammad Ali, which he used to tell vignettes. He kept saying, “and finally,” but then he would move on to more stories. In an odd reversal, it was as if the performer didn’t want the more than two-hour show to end more than the audience didn’t.

This half-hour clip from Gregory’s March 3 show in New Orleans is similar to the one in West Palm Beach.

Despite the unevenness of his performance, it was great to see a comedy legend still pushing the envelope, still as controversial and incisive as ever. Every comedian who traffics in ethnic humor today — black, white, brown, yellow or mixed — owes a debt to Gregory for paving the way. On the same day as his show, he posted a tweet that described how much the world has changed, and not changed, over the course of his life:

Gregory still has a good following in his native St. Louis.

I remembering Ft. Walton Beach. I worked for you after Paul. That was indeed an experience especially with Bess, Peggy, Bae, Angie, Debra, little Gregory,and the African dr. I was introduced to you by Liz of D.C. I truly miss being there, meeting Gay Gay, the fat brothers, YOUR NIECE, THE MEN FROM TEXAS,etc. I am now living in N.C. Take care of yourself