“Lost in Cyberspace” is the name I gave my first website, where I posted columns I wrote for a Los Angeles weekly between 1997 and 2001. The newspaper wanted me to review advertisers’ websites, but I turned the essays into ruminations on cyberspace, pop culture and current events. Today, many of the websites I reviewed don’t exist, along with the people, companies, technologies, hardware, software, and jargon I wrote about. Outdated as many of my observations are, the columns chronicle a moment in time, before Google, Amazon and Facebook, and before smartphones, broadband and flat screens, when the internet was new and a Wild West ethos prevailed.

Mea culpa: In my mid 40s and welcoming a midlife crisis, in 1996 I left my stultifying state job in Springfield, Illinois, and moved to Los Angeles, the city of second chances. I tried to become a freelance writer, and one of my first gigs was writing CD-ROM reviews for a free weekly in Burbank called Entertainment Today. This was a cheeky thing to do because I’d never played a computer game, and the only thing I knew about CD-ROMs was that my computer didn’t have a CD-ROM drive, so to write the reviews, for which I was paid $15 apiece, I would need to buy a $2,000 computer.

Multimedia reviews evolved into “Cyber Nation,” a column on another subject I was just as ignorant of — the Internet. But truth be told, one corner of cyberspace I did have some familiarity with — and coincidentally chose for my first column — was the primordial chat rooms of America Online, which was the Facebook of its time. Called the “People Connection,” users could join so-called chat rooms of a dozen or so people who would congregate based on age, hobbies, occupations, and, significantly, romantic interests.

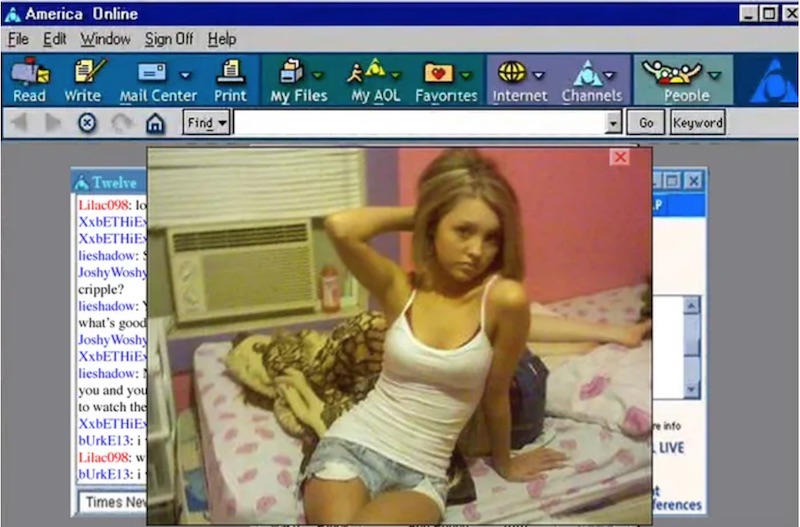

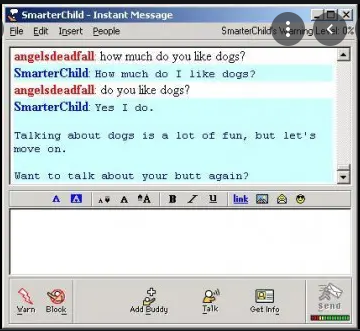

Unlike a modern video conference or Zoom meeting, with audio and video, AOL chat rooms were text only, affording the privacy to pretend to be someone else — or to be one’s true self — and to find others who shared similar proclivities. Suddenly, people with deviant desires had a way to anonymously find each other and exchange text messages exploring mutual interests in, e.g., BDSM (bondage, discipline, sadism, masochism), “gay and lesbian,” daddy-daughter roleplay, and other taboo inclinations. After hooking up in a chat room, AOL subscribers could “go private,” which meant one-on-one texting, and sometimes sexting, except without photos (which required e-mail).

While it seems downright prim, compared to the kinds of sexual interactions that take place online today, people texting erotic fantasies to each other, sometimes while mutually masturbating, was called cybersex. And people who spent too much time online having cybersex (or just surfing the web) were known as cybersluts. Just as Facebook has been accused of poisoning society by allowing “fake news” and hate speech to proliferate, AOL had unwittingly spawned a virtual sexual revolution that threatened to disrupt the social order.

Except for imagination, cybersex did not engage any of the five senses, so it was unclear if it constituted cheating. The problem was that cybersex sometimes led to phone sex, which sometimes led to real sex, which sometimes led to new relationships, but also to broken relationships and broken marriages, not to mention sexual assaults, pedophilia, prostitution and financial exploitation.

The reason I knew about AOL chat rooms was because, for a brief period of my life, I was a certified cyberslut. In fact, it was in the chat rooms of America Online that I met and fell in love with the Los Angeles woman I had left Springfield for and was living with when I wrote my first Cyber Nation column. (We remain best friends.) During our cyber courtship, our AOL bills shot up from twenty bucks to hundreds of dollars a month. Then AOL decided to allow unlimited usage for a set price, and the popularity of AOL soared, nearly crashing the internet.

The premise of my column was that sex had not merely found its way onto the internet, but was playing a pioneering role in commercializing and popularizing new technologies, from VCRs to streaming video and e-commerce. But the folks at family friendly AOL weren’t about to agree that sex had played a role in the company’s success, and by extension, the internet itself.

Cybersex and America Online 8/14/1997

by H.B. Koplowitz

When America Online began offering a flat fee for unlimited use a year ago, it seemed like a win-win-win situation. Subscribers would pay less for unlimited service, advertisers would gain millions more online customers, and AOL would reap the profits. But there was one factor the company overlooked: Cybersex.

Cybersex is nerdspeak for something that goes on in AOL’s People Connection, or “chat rooms,” where users flirt in real time by typing sometimes explicit messages to each other. While AOL provides some 200 services, from stock quotes to computer games, the People Connection may be the company’s killer app. Chat is the one service AOL does better than anyone else, and for those who are into cybersex, it is highly addictive.

AOL spokesperson Wendy Goldberg dismisses cybersex as a non-factor in AOL’s popularity, or in the massive system overload that occurred when the company switched to a flat rate. AOL expected usage to increase by 50 percent as a result of the flat rate. Instead, it doubled, in all areas, Goldberg said. She said AOL is the world’s largest on-line service provider not because of cybersex, but because it is the easiest way to get on the Internet.

Then again, she said AOL users are on the Web only 20 percent of the time, compared to 80 percent spent in AOL proprietary areas, including 25 percent in the 14,000 chat rooms of the People Connection.

PCMeter, an independent measurer of Internet use, found in April that the most-used area of the entire Internet was AOL e-mail, which transmits 15 million messages a day. However, the next highest rated AOL services were Buddy Lists (5th) and Instant Messages (6th), both chat features. The People Connection ranked 12th, compared to Computing (8th), Entertainment (13th), Marketplace (16th), Games (21st) and Today’s News (22nd).

It is easy to understand why AOL would downplay chat. In the culture of the Internet, chat is at the bottom of the hierarchy of services such as e-mail, the Web and newsgroups. Also, AOL’s chat rooms have generated a lot of controversy over obscenity, censorship, pedophiles, infidelity, even homicide.

But in going to a flat rate, AOL turned a cash cow into a loss leader, while creating a virtual modem gridlock, resulting in busy signals and pissed-off subscribers. Membership skyrocketed from 6 million before the flat rate to more than 8.5 million today. At one point 8 million AOL members were trying to dial in on only 200,000 modems, a ratio of 40 subscribers per modem, when a 12:1 ratio is considered optimal.

For cybersluts, many of whom who had a monthly AOL Jones in the hundreds of dollars, it was like telling addicts they could have all the heroin they wanted for $20 a month, then cutting the supply. Talk about panic in Needle Park!

In response, AOL invested $350 million in system upgrades. It invested millions more in reimbursing customers who sued for loss of service. Goldberg said AOL considers 20 subscribers per modem sufficient, and that “we’re getting there.”

According to Inverse Network Technology, a Santa Clara, Calif., company that rates service providers, customers trying to log on to AOL in July during peak evening hours were unsuccessful about a third of the time. Although better than the dismal 80 percent call failure rate INT found earlier this year, AOL is still a long way from the industry average of a 9.5 percent failure rate.

Ironically, if AOL was trying to put competing Internet service providers out of business by charging the same price while providing more services, the impact has been just the opposite. Because AOL’s direct lines are so often busy, more members are using the smaller ISPs to get on AOL. However, these smaller ISPs now face the same problem as AOL. The more their customers lurk in AOL’s chat rooms, the more their resources are strained.

To recoup revenue lost by going to a flat rate, AOL began selling ads that appear in the chat rooms. It also has marketing agreements with a buyers club and a long-distance phone company. But following angry protests, the company shelved a plan to sell members’ phone numbers to telemarketers. Another way AOL can generate revenue is to go to a tiered service, similar to cable TV, charging one price for basic services and an additional fee for “premium” channels. AOL recently began doing that by offering “Premium Games” for $1.99 an hour.

But rather than targeting children who play games, AOL ought to be going after the true bandwidth hogs: cybersluts who play in the adult chat rooms of the People Connection. Charging for cybersex might be harsh medicine for cybersluts. But it is in their own interest, as well as that of AOL and the entire Internet community, for them to slack off instead of jack off.