Instant Messaging 9/4/1997

by H.B. Koplowitz

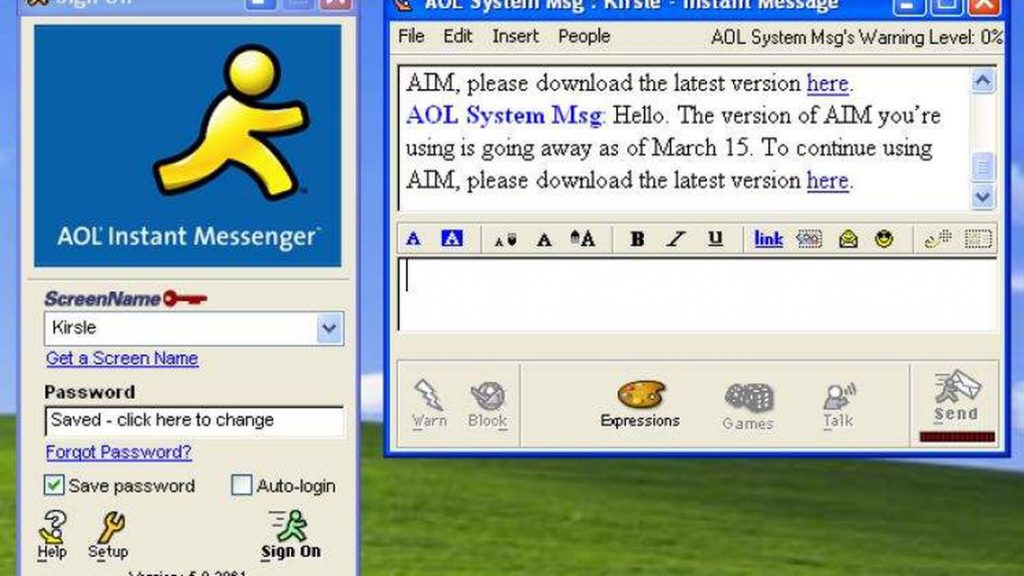

Nowadays we take for granted the instant messaging software on our smartphones that enables us to avoid talking to each other. The technology has been around since the creation of the internet, but it wasn’t until America Online introduced AOL Instant Messenger in 1997 that it caught on. A press release from a company called Excite prompted me to do my fourth column on the emerging technology, which I subjected to Freudian analysis. (AIM bit the dust on Dec. 15, 2017.)

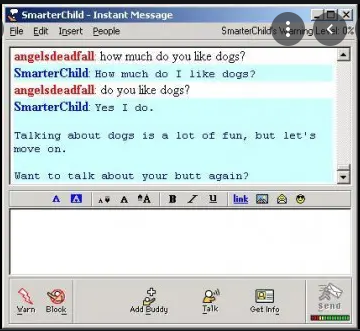

As I write this column, I am having a private online conversation with a friend. Only I’m not signed on to America Online or in some Web-based chat room. Rather, I am using a simple, free, stand-alone instant messaging software application, the latest conspiracy by the computer industrial complex to turn us all into cybersluts.

Instant messaging (IM) is like a cross between a phone call and a letter. Internet users can communicate with each other instantly and privately, like a phone call, but in written messages on a computer screen, similar to a letter, and with no long-distance charges. The software also lets you know when your friends are online and able to cyberchat.

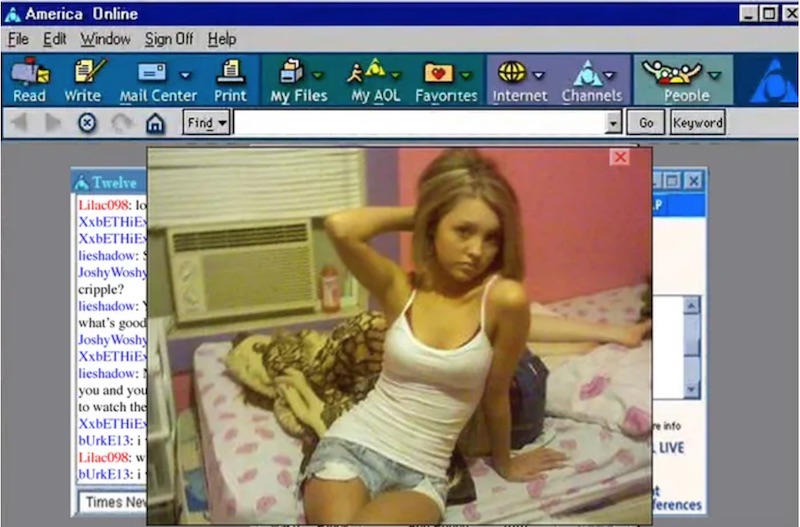

Denizens of America Online’s chat rooms are already familiar with both features, which AOL calls Instant Messages and Buddy Lists. What is new is that AOL and other companies are making IM technology available to everyone on the Internet. What is amazing is that the preferred mode of communication for cybersex is now being touted as The Next Big Thing in business communications.

Instant messaging is going to revolutionize computer communications. By enabling computer users to communicate with each other in real time, it adds a human dimension to the online experience. If you are not a subscriber to America Online, but are on the Internet, you must get IM software and make sure all your Internet friends have it as well.

About a half dozen companies have come out with instant messaging software. In a recent review by PC Magazine, AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) came in dead last. Although it has been released to the public, AIM is still in the testing phase. But AIM has one thing its competitors lack, i.e., 8 million America Online subscribers to communicate with.

Thus, even though I installed a competing software program, the Personal Access List (PAL) by Excite, I couldn’t use it because I didn’t know anyone else registered with PAL. After installing AIM, however, I had a gas contacting my friends on America Online while I was using my Earthlink account and not logged onto AOL.

Easy to install and easy to use, AIM doesn’t take up a lot of memory, so at the same time I was sending instant messages I could surf the Web or run off-line applications like word processing and spreadsheets. I could also message Web site addresses that my friends could click on and their Web browser would take them to those sites.

In addition to cyberchat and cybersex, instant messaging has many practical and business applications. “AOL Instant Messenger improves productivity, helping colleagues get in touch quickly as they exchange important information,” noted David Gang, AOL senior vice president of Product Marketing.

Eric Jorgensen, product manager with Excite, expressed similar sentiments. “There is a huge market with affiliated groups, and one obvious group is businesses.”

One advantage to PAL is you can register under your existing e-mail name, making it easier for friends to find you, while AIM requires you to create a new screen name. Excite also hopes using e-mail addresses frees instant messaging from its sordid association with chat rooms and cybersex.

Jorgensen said Excite plans to keep PAL free to consumers, with advertisers paying for the service. Excite also owns Webcrawler, the popular Internet search engine, which displays ads depending on which keywords you type in. To register for PAL, consumers must provide demographic information including zip code, gender and age, which advertisers can use to place demographically targeted ads onto the PAL screens.

The final version of AOL’s Instant Messenger also will have ads. As for whether America Online plans to ever charge for the service, Gang said rather cryptically that there are no plans “at this time.”

The bottom line is that if you subscribe to America Online you already have instant messaging. If you don’t use AOL, but are on the Internet and have other friends on the Internet, you – and they – should get IM software. For now, America Online’s AIM is the only game in town. It is available at the AOL Web site <aol.com>. If you can’t bring yourself to use an AOL product, you can get Excite’s PAL from its Web site <excite.com>. Just remember you have to get your Internet friends to use the same software.