by H.B. Koplowitz

Before entering journalism grad school in 1987, I took a summer job writing press releases for the Illinois State Fair in Springfield, and by extension, the administration of Gov. James R. Thompson. It gave me pause, because in a few months I would become a news intern, reporting on the administration I was accepting a paycheck from. Worrying about a potential conflict of interest or appearance of impropriety may seem quaint today, when a Republican political consultant like Roger Ailes could claim the cable news channel he ran, Fox News, was “fair and balanced,” or a civil rights activist like the Rev. Al Sharpton could organize a protest rally for the family of Florida “stand your ground” shooting victim Trayvon Martin, and then “report” on the rally on his MSNBC show. In my case, I wasn’t overly concerned that a temporary state government job would compromise my objectivity. But maybe I should have been, because it did change my perspective on the difference between being objective and, well, fair. (As luck would have it, the Springfield State Journal-Register newspaper posted some photos of the 1987 fair, which I have reproduced, along with the fireworks photo, which is from the 1993 fair.) Dedicated to Jim Skilbeck, 1949-2002.

Patronage Flack

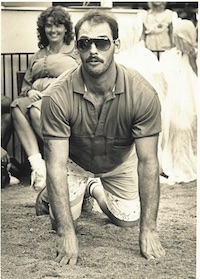

There must have been 500 people packed around the railing of the stinky smelly Swine Barn show arena at the Illinois State Fair. Waving my press pass, I pushed through the crowd and entered the media area, joining about 30 reporters lugging notebooks, microphones and cameras. Everyone was focused on a swarthy suburban Chicago man, who was down on all fours in the straw and dirt, snorting like a pig. The Hog Calling Contest was but one of the many “stories” I covered during my brief tenure as a press officer for the fair. In addition to the hog callers, I got to see the Biggest Boar, Pork King Cook-off and Sale of Champions. Not to mention the harness racing and Grandstand shows. Or backstage hot tub.

Not that everything was bucolic. The hours were long, the pay minimal, and there were also the ethical considerations. Two terms generally at odds with the journalistic profession are “patronage” and “public relations,” and my job was both. Having been a reporter and freelancer, I figured I was well qualified to write for the fair. But I never would have gotten the job if it weren’t for my friend Jim Skilbeck, whose title was special assistant to Gov. James R. Thompson. Jim and I met in 1976, when Thompson was first running for governor, as a moderate Republican. I was a student reporter at the Daily Egyptian, and Jim was an assistant press secretary for the former Chicago federal prosecutor who had shined his star by putting away some big names, including a former governor, and early in his career, “sick” comedian Lenny Bruce.

Jim had orchestrated a campaign swing through southern Illinois, and had invited the DE to send a student reporter to ride in the candidate’s RV from a cafe in Herrin to an American Legion hall in Anna, about 40 miles. I drew the assignment, and during the ride, I asked the candidate whether he favored decriminalizing marijuana. I thought I had him in a bind — if Thompson said he was against easing pot laws, it could turn off SIU students, but if he said he was for it, he might piss off the law-and-order folks in Herrin and Anna. But he casually batted my question aside, saying sometimes leaders should lead and other times they should follow the will of the people, which at the time was anti-pot.

When I got my first journalism job, at the Illinois Times, I saw Jim at a Springfield pub and started to introduce myself, but he remembered my name and what I’d asked his boss on the bus. Some years after that we ran into each other on the strip in Carbondale, tipped a few beers and took a shining to each other. He became my token conservative friend and I was his token liberal friend, though truth be told, our political views weren’t that far apart.

At age 38, Skilbeck had become Thompson’s “senior aide,” the staffer who had been with him the longest, and one of the perks that came with being the governor’s senior aide was the clout to use the patronage system to give friends jobs. In most cases, “friends” meant political friends, card-carrying members of the party in power, people who had donated money or worked for candidates. Having never donated a dime nor lifted a finger to help any politician, and having voted against Thompson in 1982, I didn’t fit into the category of political friend. But there is a subcategory of patronage, also frowned on by journalists, called nepotism, in which non-political relatives and friends of people in power get jobs, and it was my honor to be Jim’s friend.

Over the years we occasionally joked about him getting me a patronage job — I would be abandoning my journalistic ethics, and he would be using his clout to hire someone with absolutely no Republican credentials. But it wasn’t until I returned to Springfield to enter the Public Affairs Reporting graduate program at Sangamon State University (now University of Illinois Springfield) that either of us took the idea seriously. It was expediency, impulse and a bit of perversity that prompted me to ask Jim if there might be a temporary state job in Springfield over the summer to ease my transition to grad school.

His face lit up. “You could write press releases for the State Fair,” he said. Jim’s face always lit up when he talked about the fair. It was the part of his job that he loved the most, and he literally lived on the fairgrounds during the event. I had never shared his enthusiasm for the exposition, but I’d never been through the experience, either.

There was something irresistibly naughty about slipping over to the other side for a couple of months and having a fling as a patronage flack.

“I guess I’d be writing a lot of stories about livestock contests,” I said skeptically.

“That’s about it,” he said. “But you’d be at the fair.”

It was a tough call. Since in six months I’d be interning with a news bureau that covered the governor, I didn’t want to compromise my objectivity or credibility by taking a job in his administration. But I really needed the money, and besides, there was something irresistibly naughty about slipping over to the other side for a couple of months and having a fling as a patronage flack.

Ag Etiquette

The State Fair Press Office was a creature that came to life just two months out of the year. When I was there, it consisted of three other writers and an editor, who happened to be a former PAR grad student. In addition, there were two photographers and a photo editor, two messengers and two coordinators in charge of press credentials. The supervisor was Mia Jazo, a bright and energetic woman in her late 20s who had just taken over the job. Her boss was Mark Randal, the press secretary for the Ag Department.

As I became acquainted with my co-workers and those in other departments, I couldn’t resist asking them, “who got you your job?” Judging from the vague and guarded responses, I wasn’t the only one sensitive about being a patronage worker. But after some winking and prodding, it usually came out that if they didn’t know someone who was someone, their parents or someone else knew someone who was someone. Some I didn’t have to ask, like one young fellow with the same last name as a senior official in the Ag Department, who was briefly with our office until his nocturnal golf cart escapades got him transferred to another division.

Shortly after meeting the other writers — three intelligent and attractive females half my age — Mia asked us to write down which venues we wanted to cover and left us together in a room. Here it comes, I thought to myself. Livestock City. But I was in for a surprise. “I want to cover beef,” piped up one of the women. “No, I want beef,” said another.

“OK, then I get to cover pork,” said the first. “I wanted pork,” complained the third. “But that’s OK. I’ll take sheep and goats.”

My mouth dropped open. “You … like … livestock?” I blurted in bewilderment. “Sure,” they responded in unison

“Bless you my children,” I said.

Next came an icy pause. Finally, the one who got beef spoke: “So what’s the matter with livestock?” she demanded.

I bit down hard on my tongue. “Not a thing,” I said lightly. “It’s just that all you’ve left for me is the harness racing, so I guess I’ll have to take that.”

Covering the harness races mostly meant reporting the results at the end of the day, so when I wasn’t hanging out at the track, I helped cover events on the other “beats.” We reported on many of the same things as real reporters, but our jobs were mostly exercises in absurdity. Our press releases were sent to hundreds of print and broadcast media across the state and nation, but most got one cursory glance from a low echelon copy editor before getting tossed in the trash. Still, it was important that we got them right, because those that did get used sometimes were printed verbatim and unedited.

It hadn’t really sunk in for me before that the State Fair was under the Agriculture Department for a reason, and that most of the other patronage jobs went to people with an ag background who were far more qualified than I was to be working at the fair. Thanks to Jim, the Psychedelic Furs might perform for one night, but the meat and potatoes of the fair was the livestock show, one of the largest such expositions in the country. I might have known something about journalism, but my coworkers knew farm animals. They’d shown livestock in 4-H competitions and one wanted to become a farm reporter. They also knew about ag etiquette, and I soon learned to never call a hog a pig. I also learned that there are queens and there are queens. One of the writers had been a county Beef Queen, which was not a beauty contest, she emphasized, but a competition for a representative to promote the beef industry. She said she had also been an Angus Ebonette, whose job it was to go around to county fairs and hand out ribbons.

The Psychedelic Furs might perform for one night, but the meat and potatoes of the fair was the livestock show.

“Does the Angus Ebonette have to compete against other cattle princesses, like the Heifer Princess, before she can become the Beef

Queen?” I asked.

By the way she glared at me, I knew I’d stepped in something again. “A heifer is a cow,” she corrected me.

Public Trough

There are two stages in the life cycle of a State Fair press officer. The first six weeks are slow and easy, with plenty of time to goof off, followed by a bacchanalian fortnight of nonstop workdays and all-night partying. The one major pre-fair event, or pseudo-event, that the Press Office was responsible for was a press tour, during which a couple hundred media representatives were given a ride-through of the fairgrounds on open air buses, with commentary from the fair superintendent, followed by a free lunch. Its purpose was to get reporters who usually cover crime and politics up to speed on what was new at the fairgrounds. The tour was also an attempt to stir up enthusiasm and good will among congenitally blasé reporters who thought that covering the fair was beneath their dignity.

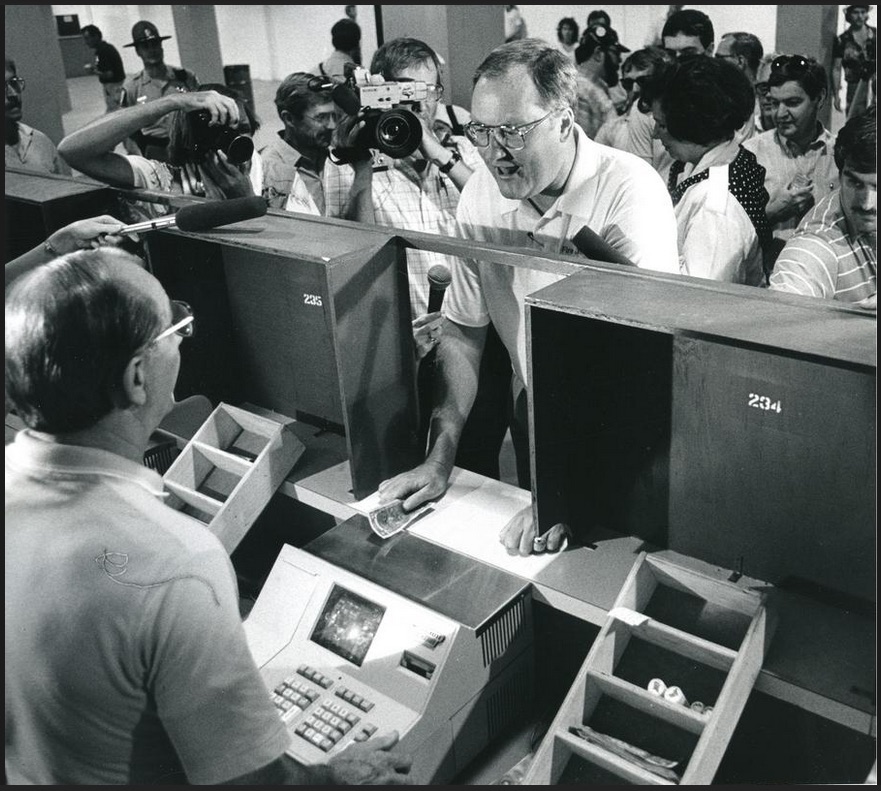

The year I was there, the arrangements were more elaborate than usual. To promote the first year of parimutuel betting at the fair, a harness race was staged. The simulation included having the reporters place fake bets at a parimutuel window, and those who won got paid with oversized two-dollar bills with Gov. Thompson’s face in the center, which the media dubbed “Jim Bucks.”

—The State Journal Register

The “Press Stakes” was Mia’s idea, and from a PR standpoint, it was a gem. The harness race gave the TV stations plenty of visuals, and subliminally, having the reporters place bets revved up their interest. The race turned out to be competitive, and as the six horses rounded the final turn in a pack and raced down the stretch, some of the normally laid-back reporters began to root their horses home. Even if most of the reporters didn’t bother to collect their Jim Bucks, they had not merely observed but experienced the emotional thrill of betting on a horse race, and that excitement came through in their stories.

Following the tour, the reporters retired to the Press Office patio for their free lunch, and I was accosted by reporter Tom Atkins of the alternative weekly Illinois Times, where I had once worked. He wanted to know if there wasn’t something improper about providing free food to people who were supposed to report objectively on the fair.

Airily, I told him that if the reporters were willing to go through the drudgery of the annual press tour, the least we could do was provide them with something to eat afterwards. But Atkins’ question had rattled me, because I still had qualms about being a patronage flack, and I was getting some bitter satisfaction from watching other journalists lining up at the public trough, albeit to a far lesser degree than I.

Tough Questions

The Press Office office was located on the third floor of the dilapidated Illinois Building, behind a giant statue of Abe Lincoln just inside the Main Gate. The third floor also provided workspaces for about a half-dozen real news organizations covering the fair, including the State Journal-Register, Chicago Tribune and Tribune Radio Network. It was also the scene of daily press conferences with venerable Fair Superintendent Merle Miller, where the first order of business was to announce the previous day’s attendance and speculate on whether total attendance would break the magic number of one million again.

Press Office employees were issued the same press passes as the real reporters, which gave us free access anywhere on the fairgrounds until 6:30 p.m., and free admission for ourselves and a guest to stand on the track during the Grandstand shows at night. Best of all, the passes granted us golf cart privileges, and golf carts were the most regal mode of transportation on the fairgrounds.

Flacks also have the pleasant but sometimes frustrating task of only reporting the good news and putting the best face on what few negatives pop up. For instance, as he had in previous years, Gov. Thompson showed up to eat the winning meal at the Pork King Cook-off. As he was stuffing his face with the winning butterfly pork chops and mugging for the photographers, Ben Kinningham of Tribune Radio poked his microphone through the throng and asked an unappetizing question: “Governor, what’s your reaction to the group in Chicago who want to chain themselves to the gate of your home to protest your stand on pending AIDS legislation?”

Between bites, Thompson said he would let them protest at his house or talk with them at his office, but not both. “I believe the private residence of public officials should remain private,” he said.

Next it was my turn. “I got another tough question for you, Governor,” I began. “How’s your lunch?”

The biggest hard news to come out of the fair was a Sunday night storm that blew down tents, stranded riders on the aerial lift and injured several people. The Press Office didn’t issue a press release on that incident. Nor did we touch the porta potty scandal. Seems a disgruntled bidder on the fair porta potty contract leaked a story, appropriately to a newspaper nicknamed the “Urinal-Register,” that the winning bidder’s potties were substandard and poorly maintained.

The newspaper’s ag reporter, Charlyn Fargo, “investigated” 30 of the potties and found some were without toilet paper, light bulbs or proper drainage. Her story resulted in a state hearing on the potties and a reprimand to the owner. But further investigation also revealed that more than 100 of the toilets had been vandalized, or sabotaged, casting suspicion on the bidder/leaker who stood to gain if the other portable toilet company lost its state contract.

Livestock City

About a million people a year visit the Illinois State Fair. So do thousands of horses, steers, cows, sheep, goats, chickens, rabbits, pigeons, barrows and gilts. Their owners cart them around to fairs all over the country, trying to earn premiums, stud fees and auction proceeds. It’s also a time for the owners to get off the farm, socialize with their peers and show off their products.

Livestock expositions may leave some city folk cold, or with allergies, but for the thousands of farmers who attend the shows it is a time to take pride in their industry. It’s also not a bad life for the animals, considering the alternative. Take Dallas, the winner of the fair’s Biggest Boar Contest. Dallas was destined to become sausage until his gross obesity caught the eye of Marvin Caldwell of Littleton, Illinois, whose hobby happened to be exhibiting heftiest hogs. The half-ton Yorkshire got a reprieve from the slaughterhouse and instead toured the county fair circuit, where adoring fans showered him with affection just for mugging in his pen like the world’s biggest ham.

–The State Journal-Register

The climax of the livestock show was the Sale of Champions, a choreographed auction of the junior champion steer, barrow, wether, market pen and pen of rabbits, i.e., champion castrated bull, similarly altered hog and goat, three chickens and three rabbits, whose registered owners are 4-H members under 20 years old.

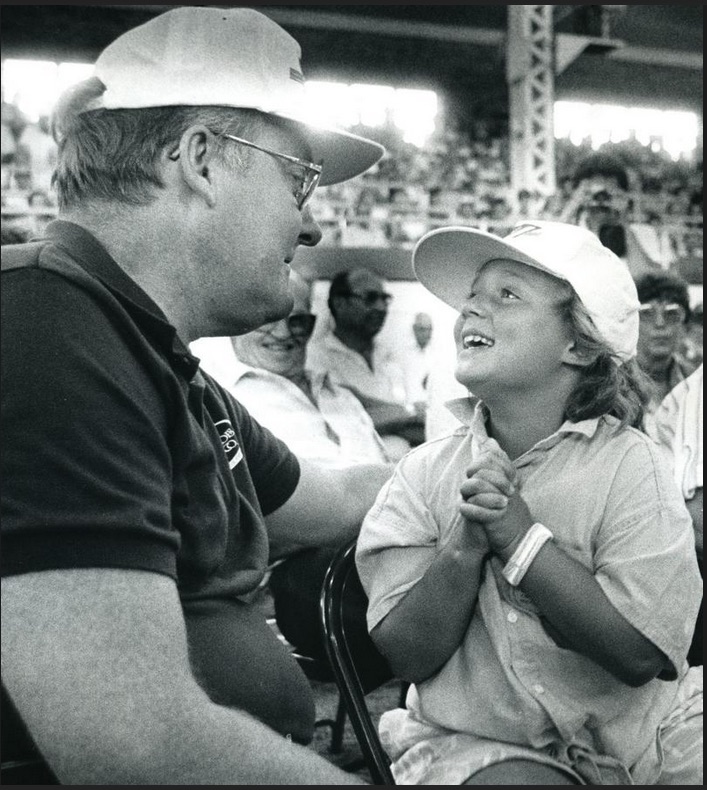

The “auction” was another of those pseudo-events for politicians, and especially the governor. The year before, Thompson’s daughter Samantha had purchased the champion rabbits (with Thompson campaign funds), to the feigned chagrin of her parents. This time Samantha was supposed to buy the champion hog, but something went wrong. As the bidding began, Skilbeck whispered to me that Samantha would buy the swine for about $9,000 — with the money coming from Chicago Bears coach Mike Ditka — and the hog would be used for a promotion at Ditka’s Restaurant in Chicago, which featured pork chops.

But things got out of control. Mother Jayne was sitting next to Samantha, cuing her to bid, but as the price neared and then cleared $9,000, Big Jim took over the coaching. And when the bidding reached $10,200, he physically restrained his precocious adolescent from raising her hand again. The victorious bidder was farm reporter Stu Ellis of radio station WSOY in Decatur, on behalf of the Friends of Macon County 4-H. “I thought Ditka was supposed to buy the barrow,” Ellis said, savoring the moment.

Typically, Skilbeck put a positive spin on the debacle. “It’s more money for the seller,” he noted.

Golf Cart Derby

Like a political convention, everybody who’s anybody at the fair has at least one laminated pass, and those who are really somebody accumulate handfuls of cards, pins and decals, which they dangle from neck lanyards, or in some cases shoelaces. The passes grant their bearers various perks, including free parking, golf cart privileges and access to press areas. With the exception of the yellow security pass, the most coveted pass on the fairgrounds was the orange “All Access” pass, which in addition to all the other privileges, provided free admittance to the reviewing stand at Grandstand shows, and most importantly, nighttime access to the backstage compound on the infield, where the entertainers hung out and the real partying took place.

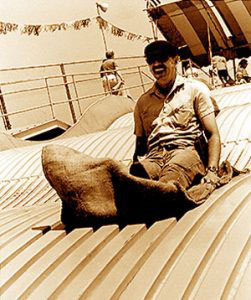

Access to the infield was through a tunnel beneath the racetrack, which had a security guard at both ends. The tunnel came out beneath the stage, where there were dressing rooms, a modest dining area with picnic tables and catered food, and offices for the stage crew. Behind the stage and inside a rickety picket fence was the compound itself, where my friend Jim and some of the other fair organizers lived in three recreation vehicles and a travel bus. Each night a bevy of friends, sycophants and potential conquests trekked backstage to make merry.

There was a large and inviting Jacuzzi that created a minor flap. The official objection was that image-wise the hot tub appeared decadent, and would reflect negatively on the governor if it found its way into the newspapers. On a more visceral level, there was concern that the hot tub filters might become clogged with illicit ejaculates.

But backstage turned out to be pretty tame. The major diversions were free booze, watching groupies trying to board that night’s band’s bus, and intermittent displays of pyrotechnics. In earlier times backstage may have been more risqué, but as one backstage vet noted, “nothing goes on anymore because backstage has become a very public place.” But it was also an oasis from the franticness of the fair, both a command post and getaway, where fair officials, spouses and friends, including a few media people, could go off the record, blow off steam and talk out of school.

Without an orange pass, the only way to get backstage at night was to be escorted by someone who had one. My efforts to procure an orange pass were stymied because before being laminated, they had the names of the people they were issued to written on the backs. Toward the end of the fair, I told Jim it was getting to be a hassle for me to find an escort every night, and asked if there wasn’t a simpler way.

We were standing in an RV in the compound that served as his home during the fair, and he picked up an orange pass that happened to by lying on a table. “Take this,” he said and tossed it to me.

When I turned it over, it read, “Governor Jim Thompson 1-A.” I held the pass gingerly. “You sure about this?” I asked.

“Don’t worry,” Skilbeck said. “He doesn’t need it.”

On the last night of the fair, the annual Golf Cart Derby took place on “the world’s fastest dirt oval mile.” The event had become quite competitive. The previous year, members of President Reagan’s Secret Service detail and staff participated, and someone broke an arm. About midnight, entertainment manager Mike DuBois appeared with a bullhorn and hummed the call to post. “Drivers, start your golf carts,” he crackled over the bullhorn.

About a dozen carts with drivers and riders lined up in front of the Grandstand and took off to the accompaniment of bottle rockets. In the minutes it took the carts to circle the track, a length of toilet paper was unrolled across the finish line, and spectators shook up beers to spray on the winner. That year’s race had a ringer in it, as a cart that had been a dog all week was surreptitiously souped up by the fair’s press secretary. Ridden by two female photographers, the fillies finished 100 yards ahead of the rest of the field.

Fairness

The fair was over, and so was my job. I began taking journalism and government classes at SSU, where the subject of patronage came up periodically, causing me to cringe. But I didn’t feel like my interlude as a patronage flack had turned me into a partisan. Rather, it gave me a deeper insight into how state government works, and in many cases doesn’t work.

Besides, long before I accepted a favor from Skilbeck, my objectivity had been compromised by our friendship. I could no longer view him as a faceless news source, but as a flesh and blood human being, with feelings and a personal life that could be affected by what I wrote. And it occurred to me that maybe that wasn’t a bad thing. That when reporting on criminals, celebrities and politicians, instead of viewing them as grist for the daily news grind, they should be treated like human beings. That doesn’t mean pulling punches or fudging facts, but reporting on them fairly, without cheap shots. It means objectivity with a heart, and I make no apologies for that.